How Frog Brains Are Helping to Understand Autism

A UCSF researcher is using gene editing to unlock new clues about the origins of autism.

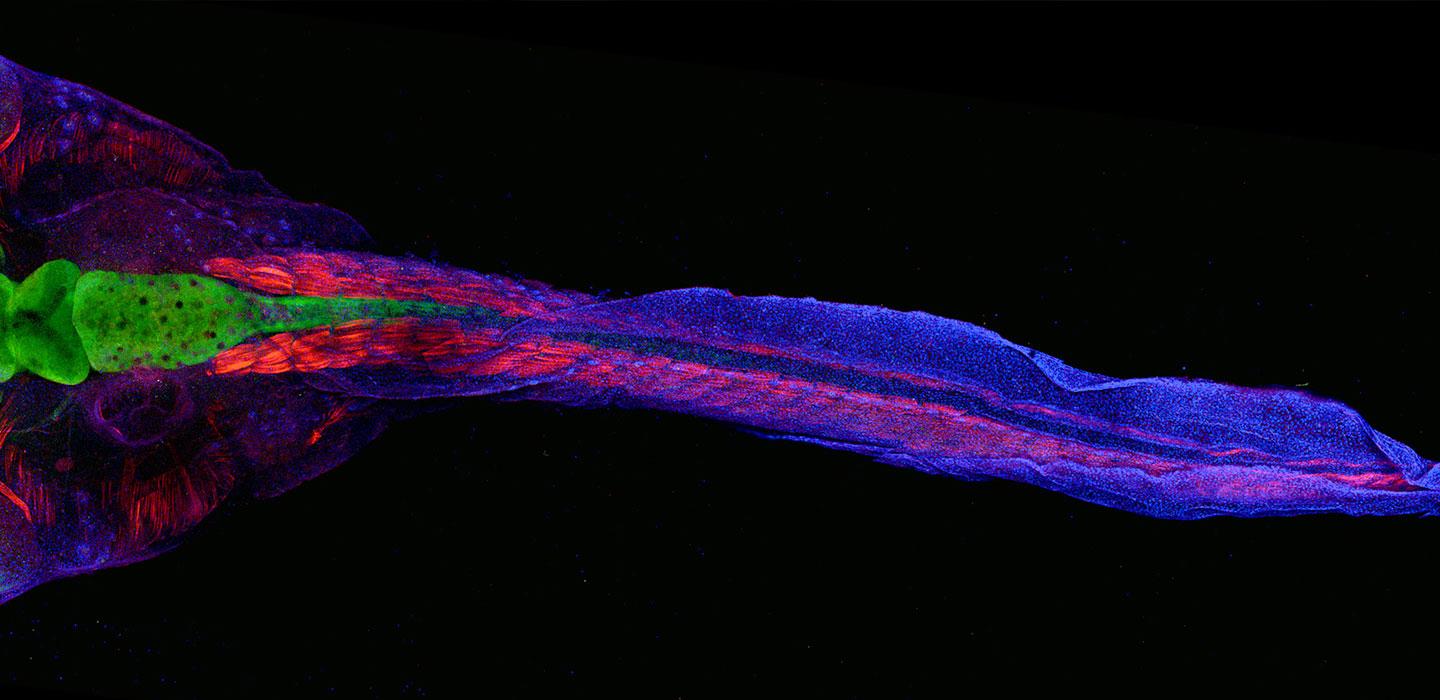

Colorful imaging helps Willsey assess the results of her work. This tadpole’s brain and neurons are shown in green, muscle in red, and DNA in blue.