Immigrant Children at Risk

How our hospitals play an integral role in their safety and healing

Juan was 14 when he fled abuse in Guatemala. He’d left school because his father forced him to spend long days laboring in the fields. A local gang was targeting him for recruitment. Verbal abuse from gang members had escalated into physical assaults and death threats.

Juan – whose name has been changed to protect his privacy – felt he had no other choice but to make the dangerous, 1,200-mile journey to the US. Once here, he was advised to apply for asylum. Juan was referred to legal services, which scheduled a forensic exam at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland to document the physical and psychological manifestations of abuse – crucial evidence to present with his asylum application.

At the hospital’s Pediatric Human Rights Collaborative (PHRC), Juan told his story to psychologist Will Martinez, PhD, one of many providers who volunteer their time at the program monthly. During the physical exam, pediatrician Raul Gutierrez, MD, noticed scars on Juan’s head, arms, and chest. Most were from gang beatings, Juan said. The rest, he admitted, he had inflicted himself.

The scarring was consistent with Juan’s recollections of abuse, and the self-harm indicated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Martinez and Gutierrez summarized their findings in a report for the asylum judge and then called in the collaborative’s social workers to get Juan psychiatric and medical support. All in a day of unpaid volunteer work.

A Center of Excellence is Born

In 2016, amid a surge of anti- immigration rhetoric and policies, a group of UCSF Benioff providers became deeply concerned about their immigrant patients. How would the national climate impact these children? What could they do to protect them?

Gutierrez, pediatrician Zarin Noor, MD, and social worker Chela Rios-Muñoz, LCSW, took action. They applied for funding from the hospital, Alameda County, and private donors, and in 2019 launched UCSF’s Center of Excellence for Immigrant Child Health and Wellbeing, an initiative to address the health of immigrant children through advocacy, education, and evidence-based clinical services.

First, they coordinated stakeholders to implement the Safe Hospital Policy, which articulates UCSF’s response to raids from US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and began training future pediatricians on how to provide trauma- informed, culturally responsive care. Next, they partnered with UCSF's Human Rights Collaborative, a student-run program that provides medical and psychological forensic evaluations for asylum-seekers.

“But the trauma that younger patients experience is very different,” Noor says. “How they experience and remember trauma really depends on developmental factors, so we worked with that team to create pediatric-specific programs in Oakland and San Francisco.”

The Pediatric Human Rights Collaborative-East Bay

Juan is finally safe, and partner organizations are providing the treatment he needs to heal. PHRC staff members follow up with him regularly.

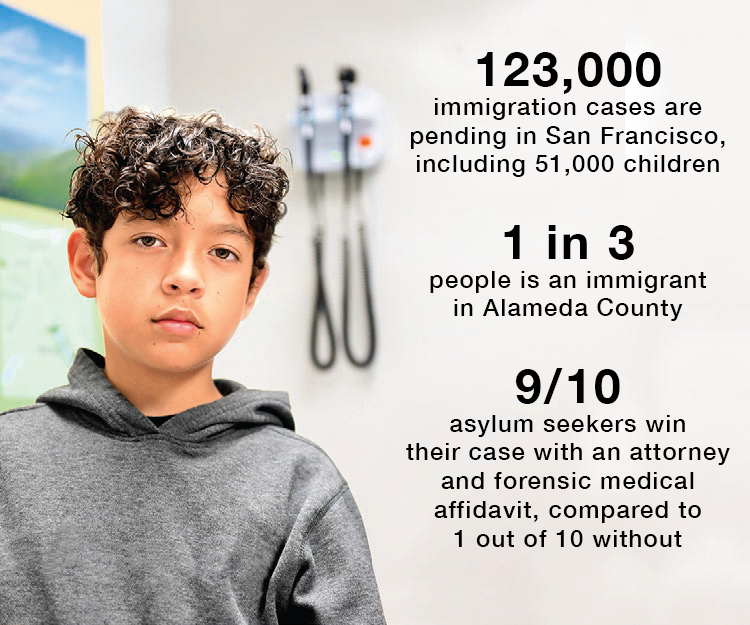

The program has a powerful impact on kids like Juan. Currently, there are over 123,000 immigration cases pending in San Francisco, including 51,000 concerning children and youth. Access to forensic examination has shown to make a significant difference in their outcomes. Ninety percent of asylum seekers who have an attorney and a forensic medical affidavit win their cases, compared with 10% without these resources.

What sets UCSF’s program apart is its emphasis on trauma- informed and culturally responsive care specific to young people. Providers recognize the impact of trauma on children’s lives and respect each patient’s unique background, fostering deep connections between providers and patients and encouraging kids like Juan to open up, and in doing so, strengthen their cases for asylum.

The work is conducted in close partnership with legal providers, who initiate the asylum process and refer clients to the PHRC; and community-based organizations, which provide lifesaving follow-up care.

Everything is done by volunteers. The collaborative’s pediatricians, psychiatrists, medical students, and social workers work pro bono one Saturday a month. Their contributions are deeply personal: Many come from immigrant families themselves and built their careers on a desire to give back.

“This work really fills me up,” says Noor, whose family immigrated to the US from Afghanistan when she was 5. “This is why I became a doctor. Knowing we’re able to make a difference for these children is amazing.”

More Kids, More Clinics

Globally, millions of young people are displaced or living as refugees. Political unrest, climate change, and violence and abuse related to gender, sexual minority status, or ethnic background are all increasing.

Martinez says he sees many kids arrive with PTSD, anxiety, and depression, and the work can take a toll on the care providers too. “The need is just so massive,” he says. “It feels like when you plug one hole, 10 more appear. It almost seems unstoppable.

“What helps me is knowing I’m working with folks who are trying to make a difference at a higher level,” Martinez continued. “People who are thinking about building a system of care around these kids – for asylum and everything else they need: medical and psychological care, housing, legal support, and on and on. This is a whole generation of children who can contribute to our society, but first we need to get them the help they need to heal.”

Noor says philanthropy remains central to their ability to continue the PHRC and care for the rising number of children in need. “Insurance doesn’t reimburse for this,” she says. “The providers do these evaluations in their free time. But we rely on philanthropy to pay our administrators and provide patients with transportation and meals. With more financial support, we could help even more kids.”

For information on how you can support the Center of Excellence for Immigrant Child Health and Wellbeing, please contact Myhana Kerr at [email protected].