Nothing Short of a Miracle: An Epilepsy Story

Every hour. That’s how often Lew Parker had seizures on the worst days.

Lew’s parents, Jen and Vic, walked through life in fear. They spent their days in a constant state of vigilance; the specter of a medical emergency lurked around every corner. They stopped traveling and going out for dinner. They were afraid to drive with Lew in the car. His three older siblings came to see the world – and their lives – through the lens of their little brother’s condition.

"It flattened us," Jen says. "It was always a little scary at our house. We knew something devastating could happen at any moment."

But the Parkers also knew they were lucky. They could afford to pay out of pocket for medicine, special education, family therapists, and around-the-clock care. A night nurse stayed at Lew’s bedside in case a seizure struck while he was asleep.

"And even so, we barely slept," Jen recalls. “Even with all that scaffolding, we barely held it together."

Coping with Epilepsy

At birth, Lew seemed healthy. Over the next three years, he developed normally and hit every milestone: He talked and walked and dribbled a soccer ball on time. He just had the occasional seizure when he got sick.

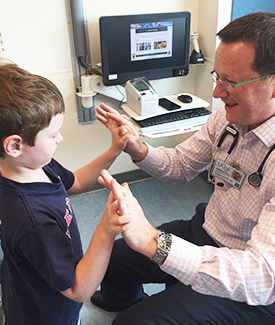

On their own, brief febrile seizures – convulsions in children often caused by a spike in body temperature – are common and without long-term consequences. But the pattern concerned Lew’s neurologist, UCSF’s Joe Sullivan, MD (pictured right with Lew), who recommended genetic testing. Lew’s test results revealed that he suffered from a severe form of epilepsy.

Over the next seven years, the seizures increased in intensity and frequency. Available medications didn’t work, and the side effects were physically and cognitively debilitating. Lew’s development became delayed. He spoke less and less.

But Dr. Sullivan was determined. He experimented with new drug combinations in a complex and delicate process of trial and error. He enrolled Lew in a clinical trial testing a novel therapy. And he showed up for the Parkers in ways that went far beyond medicine. He was the family’s rock.

“Dr. Sullivan is unique,” Jen says. “He is clinically excellent and he’s an empath. He cares so much. He became one of the most important people in our lives.”

Finding Meaning

The Parkers weren't alone. Dr. Sullivan helped many of his families navigate the daily challenges of caring for a child with epilepsy – everything from arranging extended childcare and transportation to the hospital to accessing experimental drugs, psychological care, and special education.

Over the years, Jen and Vic learned how essential this was for struggling families. At an epilepsy support group, Jen met parents who had traveled to UCSF from the Central Valley with five children in tow because they didn’t have childcare at home. Other parents spoke about watching their children 24 hours a day, seven days a week, without any outside help. They missed work and lost income. The school system was impossible to navigate. Their mental health deteriorated.

The Parkers saw how deeply Dr. Sullivan cared for these families – how he simultaneously provided world-class clinical care, led potentially lifesaving research studies, and offered emotional and logistical support to parents with far fewer resources than their own.

Jen and Vic had reached a low point with Lew’s condition. “The wheels were coming off,” Jen says. “But we had to find something positive to do amid all the stress.”

As a first step, they funded a research coordinator to help Dr. Sullivan advance promising clinical trials and bring new therapies to patients.

Then they helped launch the Pediatric Epilepsy Center of Excellence (PECE), a groundbreaking model of wraparound care for families affected by epilepsy. PECE provides access to innovative treatments, as well as psychological care, educational support, and a patient concierge who ties it all together.

Dr. Sullivan says PECE is a crucial part of his work. “Now we can address the whole patient, the whole family, the whole day, the whole week, better than our group of physicians and nurses could ever do alone.” PECE has become a model of care that UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals hope to replicate across its programs.

Lew’s Transformation

After years in distress, Lew finally experienced a turning point at age 7, in 2017: Thanks to a groundbreaking clinical trial, Dr. Sullivan identified a new drug that worked. After Lew received it, a few days passed without a seizure, then a week. A month. A year. In the past five years, he has had only one seizure.

Lew is now 13. "His transformation has been profound," Jen says, “like someone plugged him in.” After years of barely speaking, he’s talking nonstop. Last year, he started reading. He makes up stories and articulates ideas that astound his family. He lives in the moment. He’s funny. He’s happy.

Through it all, PECE has been a lifeline. Working with Dr. Sullivan, listening to families, and hosting fundraising events have given the Parkers another purpose. In 2022, they took this work a step further by establishing the Murphy Parker Endowed Professorship in Pediatric Epilepsy, which will secure PECE’s leadership, research, and service for years to come.

“I look back and think, I don’t know how we got here,” Jen says. "There are no guarantees, but it feels like nothing short of a miracle. That’s all thanks to Dr. Sullivan."